When I consider how babies fit into — and through — a maternal pelvis I view it from three perspectives: midwifery, bodywork and yoga. As a midwife I generally know more about birth than many bodyworkers. As a bodyworker I know more about how, anatomically and bio-mechanically, a baby fits into and ultimately through a maternal pelvis – more than than some midwives. This is about optimal fetal positioning – or lack thereof.

As a yoga teacher who has these other two areas of expertise, I have some idea of how to move the parent in order to give the baby inside more opportunity to move. I would say that most difficult births have something to do with less-than-ideally positioned babies. This is not just breech. These malpositions may be subtle and they are usually longstanding — beginning days, weeks or months before the onset of labor.

Last week I wrote about why so-called engagement is a pathological condition that potentially adversely affects the birth process and subtly or overtly affects the condition of the babies after birth. I explained that it is primarily caused by seated occupations and seated lifestyle for pregnant people. If you haven’t read it, you should. The link is here.

This week I’m going to tell you about more maternal conditions that contribute to these stuck babies. I’ll also give you a little advice about what you can do. Hint: bodywork and movement factor heavily in the solutions to these problems.

First, take a guess. Do you think there are more maternal factors, more fetal factors or more cultural factors contributing to stuck babies? File your answer away and you can do the tally in two weeks when I unveil part four of this story — the cultural factors that contribute to fetal constraint. Next week will be part three, the fetal factors. Part five (yes, there will be a part five) will describe labor-related problems resulting from stuck babies. Hint: It’s lots more than just cesarean births. Part six is about the actual effects of stuckness on the babies themselves. These are things we notice after birth such as torticollis.

The Maternal Factors

It’s Not CPD

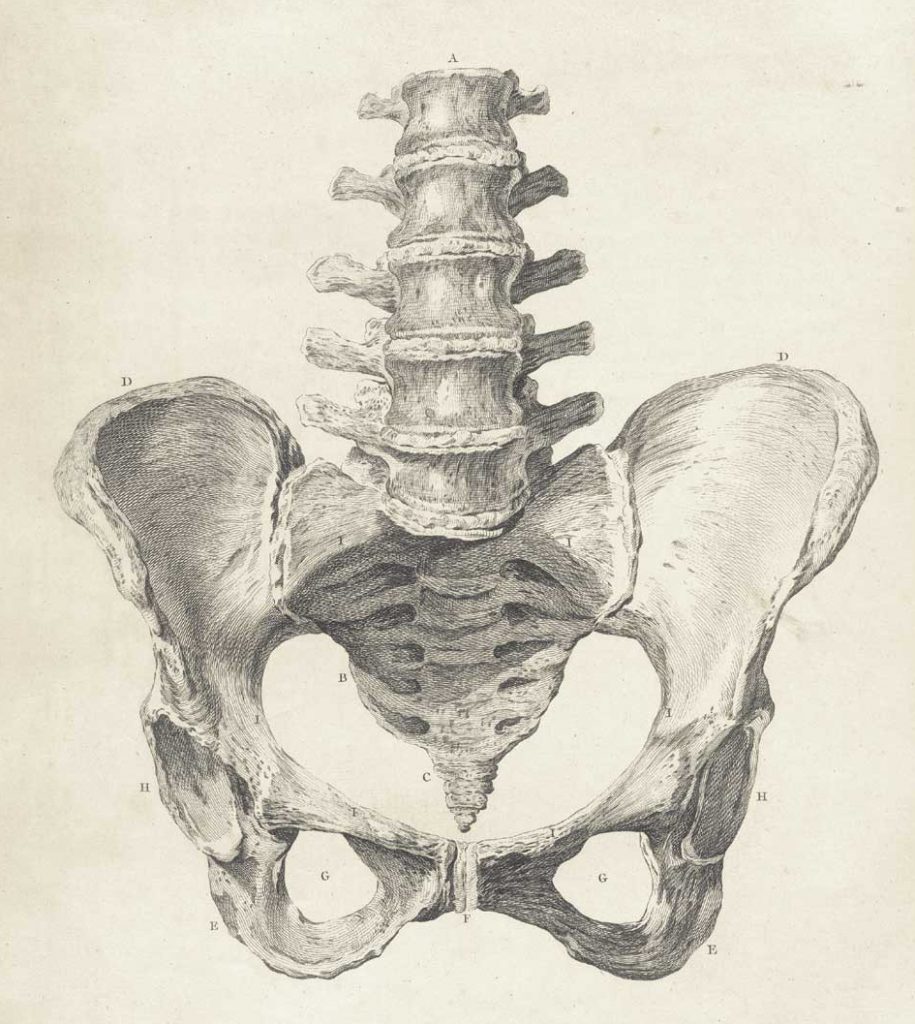

Some people have differences in the bony pelvis that contribute to baby stuckness. We’re not talking about that garbage pail diagnosis of cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD). As I explained last week, CPD isn’t a big head or a small pelvis. It’s a baby head that would fit nicely if only it was pointed in the right direction (think asynclitic, military or OP presentation).

Weird Pelvic Stuff

This is the really weird stuff that hardly ever happens — like you had rickets as a child (due to extreme vitamin D deficiency) or fractured your pelvis as a teenager and you now have a bunch of hardware holding everything together. There isn’t much you can do about the things on the weird stuff list. You do what you can to mobilize the parts that will move and keep your fingers crossed.

Ordinary Pelvic Stuff

Sometimes it’s less weird. It can be something like a stuck sacroiliac (SI) joint. Did you know that your pelvis has joints? They are supposed to move – especially in the birth process. If they don’t, birth can be a rough ride for both participants. In general, joints become more unstable in pregnancy. That’s so your pelvis will move like crazy to get your baby born. Sometimes those joints move a lot during pregnancy and get stuck in the process. When this happens, you may be able to yoga your way out of it, but probably, it’s time to see an osteopath, physical therapist, chiropractor or other bodyworker who can get you unstuck so you baby doesn’t get stuck. The midwife in me says do both yoga and bodywork (the belt and suspenders approach). Read more about posterior pelvic pain in pregnancy here.

Pelvises have similar, but different shapes overall. As different as we look on the outside, the same thing is true on the inside. We humans are all similar with unique individual differences. These different, but normal pelvis variations rarely cause problems.

The Support Structures of The Uterus

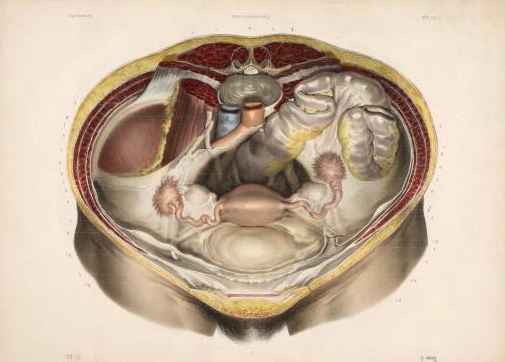

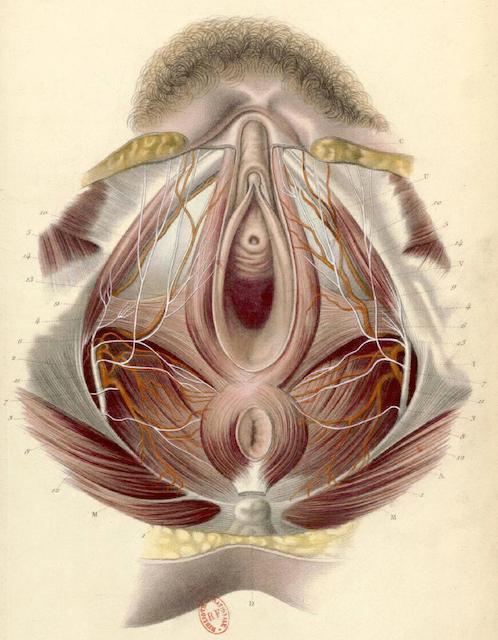

Some people have a lack of mobility in the so-called ligaments that support the uterus and the associated female reproductive and pelvic organs. I use the term so-called because, technically, ligaments connect bones to bones. This is simply not the case here. Nevertheless, they are called ligaments. Really, they are fascial structures. All of the whitish stuff in this old-timey illustration is fascia. It surrounds, envelops and in some cases permeates the muscles, organs and other structures in the pelvis.

One of the many functions of fascia (because it’s slippery) is to allow adjacent structures to glide against each other. This is really important. The old-timey illustration isn’t entirely accurate in that there is no actual empty space between the structures. The spaces are included in the drawing so we can see the various parts better. In reality, everything in there is tightly

packed and touching. All of our body parts are supposed to move independently of their neighbors. When they don’t, we have problems. Glide matters.

We give different names to these so-called ligaments like round ligaments, broad ligaments or utero-sacral ligaments, but it’s really all one interconnected fascial structure. Adhesions or restricted mobility in one place can affect movement somewhere else. This one is a biggie. This can inhibit a baby’s ability to move because the uterus and other pelvic organs can’t move normally. Trust me. That’s a bad place for things to not move. It’s like squeezing a balloon.

Speaking of balloons, another way to visualize this could be to imagine the uterus as a hot air balloon with ropes attached to it. If we tug on one rope it has an effect on all the other ropes. It also has an effect on the size, shape and orientation of the whole balloon.

Uterine Differences

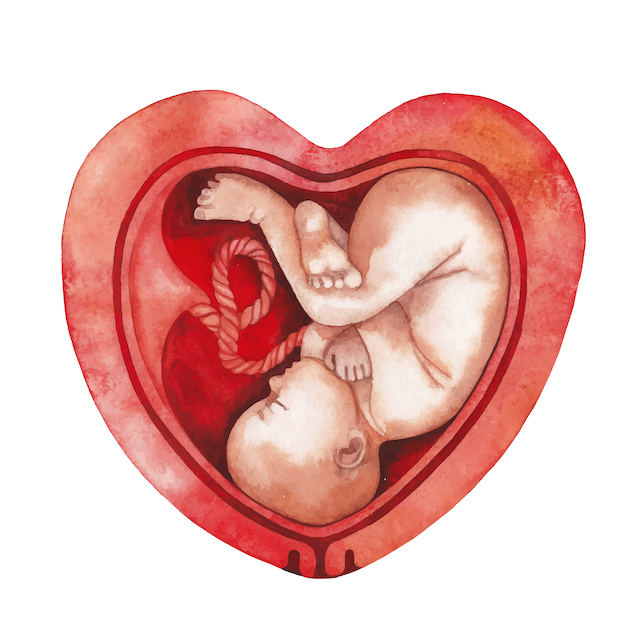

Some people have a heart-shaped uterus or one that has two separate sections divided by what’s called a septum. This is called a bicornuate uterus. These and other anomalous shapes can make it harder for babies to move into more ideal positions. There isn’t much we can do about these things. Although, keeping the parts that can move mobile may yield a better outcome.

Some babies share the uterus with fibroids which are non-cancerous tumors. If fibroids grow big enough or are in certain locations during pregnancy, they can interfere with baby movement and ultimately interfere with normal birth. If they’re big and high in the uterus, they can interfere with a baby having the space to turn into a head-down position. If they’re big and down low, they can block the way out when the time comes.

Uterine Scars

Some people have a scar on their uterus. One way to get one is to have a cesarean birth. You can see the skin scar in this picture, but this person also has a scar on the uterus. Scar tissue simply does not move as well or the same way as surrounding tissue. It could be one source of a potential problem.

Abdominal Organs

Some people have restricted movement in their abdominal organs — stomach, liver, intestines, etc. — that give a baby less room to grow upward into that area. What’s a baby to do? They grow down, deeply into the maternal pelvis or outward toward the rest of the world. Both scenarios are less than ideal and present their own particular problems for birth.

Focused, specific manual therapy can address these things. In a perfect world these issues would be addressed before pregnancy. In fact, these same things — both restricted abdominal and pelvic organ movement can play a role in infertility. It makes sense, right? We need better movement for improved blood flow, nerve conduction and overall normal function.

Can we do this kind of bodywork during pregnancy? I’m going to commit heresy here and say that it’s good to do it. I have been doing it for years. I teach it, too. The prohibitions against it were established by someone (probably an early osteopath) way back when, who didn’t actually treat pregnant people and who saw them as frail beings inhabiting bodies that were likely to go haywire at any moment. This myth has been passed from teacher to student for a very long time. I remember sitting in a visceral manipulation class as a student and hearing the teacher say, “Don’t do this on a pregnant woman.” I said to myself, “Sorry, I’ve already figured out how to position her on the table.” The bottom line is that bodywork and manual therapy can help.

There is a kind of abdominal massage called Sobada. It’s done by traditional midwives and healers in Central and South America and Mexico — perhaps becoming a lost art. The whole idea during pregnancy is to do it regularly. It is a vigorous massage done by a traditional midwife with the intention of positioning a baby correctly. This is a regular part of pregnancy care for some women. I remember talking with someone who lives in the Bay Area who during her pregnancy sought a person who could do Sobada for her. She asked her mother’s gardener who asked another person who asked someone else and so on until she found someone who could do Sobada. It was totally underground.

Muscles on the Inside?

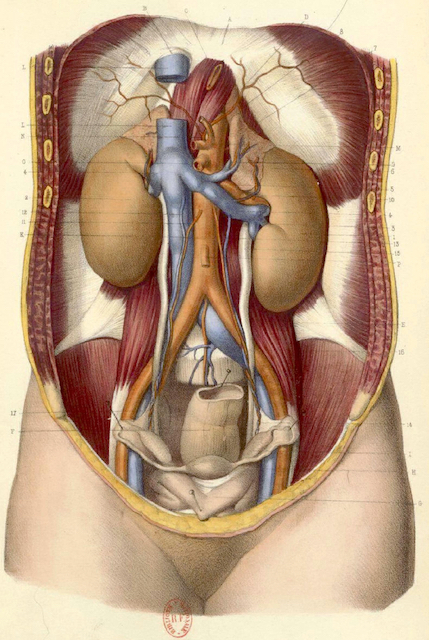

Some people have restricted movement of the iliopsoas muscle group. We all know we have muscles near the outsides of our bodies. These are deep on the inside. The first one is the psoas. The P is silent. There are two of them. In this illustration you can see them peeking out from behind the kidneys (the kidneys are the things that look a little like smooth beige potatoes – at least in this illustration). They make their way all the way down through the pelvis to a special place somewhere near the top of the femur (thigh bone) called the lesser trochanter.

Down in the pelvis the two fan shaped muscles (one on each side) called the iliacus line the inner surface of the big flat bones that make up the back and sides of the pelvis (the ilia). They also dive down through the pelvis and end up approximately in the same place as the psoas — the lesser trochanter.

Whole books have been written about these muscles. There is great speculation about whether the psoas should be classified as a muscle at all. Some think it is a sensory organ that happens to have muscle tissue — like the tongue, but I digress.

What’s important here is that imbalances in the length and strength of these muscles play a role in babies getting stuck in the maternal pelvis. They are also key players in the birth process guiding a baby’s way out. Interestingly, when a birthing person has epidural anesthesia it renders these muscles flaccid. They can no longer guide the baby in the right direction. Food for thought.

What helps? You guessed it. Yoga and manual therapy.

The Pelvic Floor

Who among us doesn’t have baggage “down there”? There’s a lot of talk these days about weakness in the pelvic floor. The general response is to squeeze everything down there and hope for the best. The problem with that is lots of people really don’t have weakness. They have what we call hypertonicity. Squeezing everything down there and hoping for the best makes it worse. That’s right — too tight. The muscles pull the bones together as far as they will go and there’s nowhere else to go. Then what? You leak urine and maybe squeeze even tighter, making the problem even worse.

Some people have both low tone and too much tone in different areas. It’s important to have a healthy balance of strength and ease throughout the pelvic floor.

Still other people have neither tightness nor weakness, but they lack normal ability to fully recruit or connect with the muscles of the pelvic floor. Of course, there are many other pelvic floor issues that can contribute to baby stuckness. How do you find out what you have? Get professional help. There are physical therapists, chiropractors, massage therapists and others who specialize in evaluating and treating pelvic floor issues.

There are also specific yoga practices that can help relax or strengthen the pelvic floor. An ideal practice would be done after you know for sure which scenario you have and where. Your yoga practice for your pelvic floor would be customized — maybe relaxing one side and strengthening the other, for example.

Take a look at the image of the pelvic floor muscles. Notice that they are generally arranged in a diamond shape. The front of the diamond is where the pubic bones come together in the front. The back of the diamond is the tip of the coccyx (tail bone). The two sides are the sitting bones (ischial tuberosities). All of the muscles connect either directly or indirectly to these bony landmarks. Remember, the job of muscles, generally, is to move bones. Imagine how restrictions or tightness could play a role in getting a baby stuck.

Unless you get surgery to get your baby born, you are faced with finding your own answer to the age old question of how do you get such a big thing through such a little hole? Most of the time it works. Awareness is key.

Here’s an awareness exercise. You can do it in any position, really — seated, standing or reclining. When you breathe normally you can feel your pelvic floor move. When you inhale it should bulge out a little. When you exhale it should retreat back towards the inside of your body. These are subtle movements. Simply noticing this can give you a head start on knowing whether you have a problem here. Maybe one part doesn’t move as I described. Maybe yours sucks in when you inhale — like a gasp. These are all indications for getting some help. Pelvic floor health really matters for your pregnancy, your birth, your sexual health and your life.

Obviously, there are other maternal factors that can contribute to stuck babies. These are the greatest hits list. I hope this post has been helpful. Until next week…

Love,

Carol